In 2004, for the launch of World of Warcraft, I was in college, enjoying the benefits of a lightning-fast internet connection. When WoW came along, I was burned out of MMOs, having had a string of intense experiences paired with my classwork. I wanted something light and casual, and while everyone was talking about how awesome WoW looked, I was in the camp deriding its cartoony graphics and lack of player-controlled features– I’d just come from games where I could build entire cities, and the idea of “questing” to level up brought back memories of Everquest’s somewhat laughable chat-to-NPCs system.

I got into WoW’s beta and immediately fell into my old tricks, because I knew it was ephemeral and would get wiped. I rolled on a PvP server, burned through levels, and became immediately disappointed with the lack of PvP features. I could fight and kill other players, but there didn’t seem to be much of a point other than bragging rights. It was fun for a little while, because I played a class (warlock) that, in beta, was an unstoppable PvP machine and could feasibly take on parties of players by themselves, but outside of the fun of getting into fights I shouldn’t be able to win and coming out on top, there wasn’t a lot going on for someone who’d just come from multiple PvP games. I decided this wasn’t going to be a game to test my skill in, but it had some very cool stories so it would make for a good roleplaying game.

Come the game’s actual launch, I jumped in very casually, testing out a few characters I thought might be fun to play before settling on one, the rogue that a lot of people are familiar with. I started up a small but close roleplaying guild (themed around my old PvP class choice from Shadowbane), would write and play out stories with the group and with other people I met, and mostly had a leisurely route up to max level. As I got close to the level cap, my old instincts kicked in because I had a guildmate who was already max level and wanted more people to group with. I burned through the last 10 levels and immediately started running dungeons. It quickly became apparent that this was the skill focus I’d been looking for, and I started making a name for myself as a group organizer, putting dungeon parties together and running the groups.

I spent enough time in those dungeons that I was able to pick up rare gear– I never got the pieces I *actually* wanted, but I picked up things that were just as good and that forced me to look at stats in the game differently, which would give me an edge later on.

Flash forward a few months. The rest of my guild and friends had caught up to the level cap and we’d fallen into a pattern of running things together. We were in pretty good gear and had gotten used to working with one another, so when we saw an open invitation in a major city’s general chat for a raid team, we signed up. We kept chatting in our little group, since we suspected that it was going to be a tragic failure (we’d had enough bad pick-up group experiences that we were pretty jaded about players we didn’t personally know), but we jumped into this raid as a full group and rapidly all died… to the first pull. For an hour or so, before enough people had dropped that the group disbanded.

We had our laughs and called it a night, but when the call came out again for a probably-doomed run, we laughed again and jumped in. The cost of repairs was worth the laughs, and we weren’t doing anything else.

Within a couple of weeks, we’d stopped dying to the first set of monsters in the raid and had started (slowly) moving forward. Success begat stability, and people hung around because maybe this was going somewhere. We got to know regulars, individuals who’d joined the group. We were slightly more outspoken than others, because we had our own little group as a support structure. We became anchors in the group very quickly.

I fell into old patterns, analyzing the groups and making quiet suggestions to the person in charge. Raiding in WoW was like a mix of raiding in EQ and keep sieges in DAoC, so I had some idea of what I was talking about and my suggestions were successful enough that they started getting listened to more. I also got to know more of the people in the group, and started adjusting my suggestions to fit.

Our raid was a late-night group, well past the usual primetime hours, which meant we had a lot of west coast players and Australians in our group, complete with lag issues. This healer isn’t necessarily as strong as that other healer, but has faster reaction times. This tank is geared really well but is bad at stance dancing. This DPS is really competent but has an ego, this other one could be just as good with a bit of encouragement, without the ego problems. These people are totally awake and functional at 1AM and are raring to keep going; these other people aren’t. I took all of these observations in from my position as a participant but not a leader and passed them onto the group’s leader.

I quickly became the “personnel manager” for the raid, and started getting pulled into “officer” conversations, until I had an important say in a lot of various things. The group’s leader was extremely organized and very structured, but hated confrontation and had a hard time dealing with people whose personalities he liked but who weren’t performing well. Filling a need, I wound up being the person who’d talk to people behind the scenes and make sure they were okay, and help them get up to snuff if needed. I wound up learning a lot of other class’ mechanics than my own to help with this, and it gave me an edge in working out strategies.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the need to coordinate and motivate people without any tangible, reliable reward structure was a non-trivial problem. The only thing anyone was assured of in a given night’s raiding was a potentially fun time and an increasingly-expensive repair bill. Really exciting loot was a possibility, but a given boss might drop one or two items, and a raid had 40 people. Even assuming a full clear of the first raid (which took us months to accomplish), that’s 10-15 drops total per week split among a group of 40 people, and that’s the ideal case where there’s no repeated drops that no one needs (very rare). Keeping people motivated in that kind of environment was my job, and I took to it because it needed to be done.

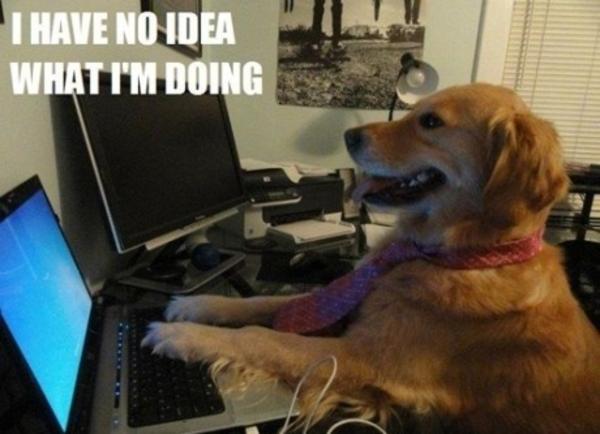

Most of my strategy for this revolved around being personable and cheerful. I knew that pushing people too hard would drive them away; there wasn’t much tangible motivation to be had, and while someone could slack off and not be noticed, if too many people were doing it we’d fail, which often happened. I was one of the first to download and install performance-tracking addons, running them behind the scenes so I could check on people. In one particularly notable case, I had another raid member set as my focus target so I could watch their resource bar. Every attack in WoW consumed some of a given resource, so watching resource bars could often be an indicator of performance and attention. In this case, I would watch the resource bar dip slightly at the start of a fight, refill, and never move again in the next 5-10 minutes of combat– a clear indicator that the person was doing next to nothing.

When I brought this up to that player privately, I got some apparently-genuine contrition and a marked performance improvement the next night, followed by an identical dropoff the night after that. It became apparent to me that this person was only going to put work in if they were directly being watched, and with 40 people to monitor, they weren’t worth the energy. I slowly upped the stakes. I’d spoken to them privately and that proved to be ineffective. I suggested replacing them to the group’s leader, who was averse to the idea of booting anyone. They were clearly holding us back, but I was limited in my tools to deal with them. I took a slightly different tack, and called them out in the raid, while they were slacking off. There had been an ongoing chat conversation that the underperforming player had been a part of while not actually participating in combat, and I called them out for spending time chatting rather than actually helping us.

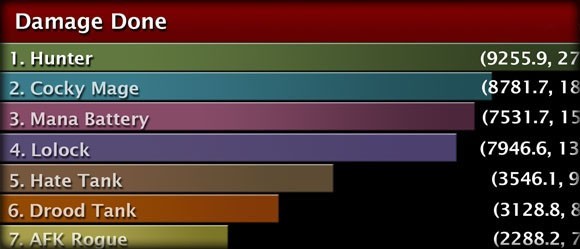

The defensive denial response was immediate, which I’d suspected would be the case. Being called out directly was a lot different from being spoken to privately, and the player in question hoped to trade on their popularity with the group to make up for poor performance. I knew it was likely to escalate quickly, so I immediately followed up with collected stats– the player’s entire damage-output contribution to the raid for the night amounted to less than one of our healers, who had thrown in a handful of damage spells between keeping people alive.

The raid leader was angry with me for turning it into a confrontation, but I stood by the fact that I’d done everything I could to improve performance short of that, and that the direct approach had become necessary. In what I think was intended to be an implicit punishment, I was made to find that player’s replacement– if I was going to make us kick people from the group, I’d be responsible for recruiting as well.

I already had someone in mind. By the next raid, I’d found someone who I’d already vetted at some length and who I knew could perform. His gear was significantly behind the old player’s gear, because the old player had soaked up a lot of drops while not contributing. Despite this, his performance was instantly better than the person he’d replaced, and it was clear he was really *trying*, because he could see immediately that he was behind the curve. The same stat tracking I’d used to indict the previous player was used to praise the new player, and I discovered a secondary benefit.

In kicking an underperforming player, a number of other people who’d been less invested suddenly became moreso, and this was amplified when a new, undergeared player started quickly outperforming some of the group who’d been there for a while previously and had significantly better gear. Within a few nights of kicking and replacing an underperforming player, three things happened: First, the overall performance of the group shot up, and we started winning where we previously weren’t. Second, the morale of the group improved, as did confidence in its leadership– it became clear that we were committed to the group’s success and willing to make even severe changes if needed, and it put everyone on the same page as far as the group’s goals. Third, a number of people started coming to me to ask for help in improving; many weren’t very good, but wanted to become better for the sake of the team.

It was the first time I’d been directly involved in managing people on an individual level. I’d worked with groups and directed big-picture strategies, but actually getting into specifics with individual people was a very different experience. I grew to appreciate the people who genuinely wanted to try and improve, versus those who were already skilled but weren’t inclined to listen to directions. When vetting potential new recruits, I had a fairly simple ethos: I’d rather bring in someone with a good attitude who can improve and learn than someone who already has the skills but doesn’t have a good attitude about it. We turned down many high-performing candidates because they had clear issues with ego, excessive demands, or other attitude problems, and brought in a goodly number of people who blossomed as part of the team.

More MMO stories next week, probably. It turns out I can’t tell all of my stories in a week.