In the heyday of the WWII shooter, I remember hearing a lot of people asking why on earth we were inundated with the same sort of games, and why the really big blockbusters are all so similar. It’s something I was never sure of myself, until I learned about something called Hotelling’s Location Model. Any economists reading this will likely chuckle to themselves, and will probably correct the next bit of what I’m going to talk about in the comments.

Ever driven out into the middle of nowhere? I’m talking miles and miles out, past the boonies into those little towns that don’t appear on most maps, just barely in range of maybe two radio stations, which are both playing the same country music. Ugh, you’d think they’d, y’know, play some different stuff and cover different audiences. Or, you’re checking out local restaurants and realize there are two nearly identical restaurants right next to one another. What are they thinking, aren’t they hurting themselves by being that close?

Here’s how it happens. Say there’s a beach, with a bunch of people spread out on it, more or less evenly, because they all want their space.

Laguna Beach, via wikimedia commons.

The City Council decides that it will issue a permit for one person to sell ice cream on the beach, on two conditions:

1.) The City sets the prices of the ice cream– this is to benefit beachgoers with a minimum of beach crowding, not line some monopolist’s pockets.

2.) The ice cream stall must set up no earlier than 10am, allowing time for the beachgoers to enter the beach and get settled. No parking at the entrance and advertising as people come in.

(What we’re doing here is controlling two variables: price and market. We want to look at WHERE the stall goes.)

So, here’s our beach:

Our ice cream vendor can set up on the boardwalk along the top there. Where along it does our ice cream vendor want to set up shop?

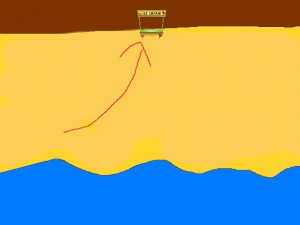

It’s easy– sell ice cream to the most number of people, which means minimizing the distance they have to walk to get ice cream. Right in the middle.

Pretty straightforward. Our ice cream vendor sells ice cream, everyone is happy, except for those people out at the edges who need to walk halfway across the beach to get ice cream. They petition the City Council to allow more vendors, and the City decides to let another vendor set up shop.

Now there are two vendors. Since each vendor is stuck with the rules above, the only way they can make more money is by selling more ice cream, which means being the closest vendor for the largest possible number of people. One of them is, inevitably, going to get to the beach first and set up shop. Where should that first ice cream vendor go?

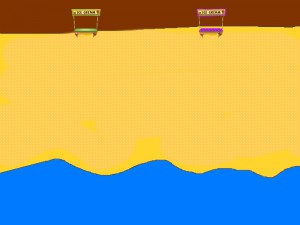

Answer: Right in the middle. These vendors are competing, they want the most customers. You might be thinking that it’s better for the two vendors to split up, maybe divide the beach in half, something like this:

It’s a good thought, and if the two vendors are colluding, this might happen. If they’re both in it for themselves, though, and the first one takes that quarter-length spot, here’s the best place for the second one:

In that position, the second one is the closest vendor to the biggest portion of the beach, and is going to come out ahead. If the first vendor sets up right in the center, so will the second vendor, just barely off to one side, and each will have half of the beach.

As the model goes, it applies to things other than physical location, too. If a clothing store offers a certain variety of products, and another clothing shop opens, they’re going to stock very similar products, hoping to hit the broadest segment of their piece of the market. If one offers a better selection (read: has a bigger chunk of the beach), it’s going to do better, and both stores will fight to keep up with one another, ultimately winding up very similar. It’s how you get the same country music on the same two stations out in the middle of nowhere, the two coffeeshops right across the street from one another, and years of military shooters, all incrementally different from the previous generation but still in nearly perfect lock-step with one another, until everyone is tired of them and a new kind of blockbuster crops up.

two nearly identical shoe shops, right next to one another.

This returns me to the bit at the top. No one here is being an idiot, the decisions are very carefully considered. The end result doesn’t appear to make sense at first, but it absolutely does once you puzzle it out. All of those military shooters, all of those country music stations, all of those shoe shops are looking out for their own best interests– and any deviation from that is extremely risky.

There’s the saying: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” It’s a good saying, but I think there’s a followup:

“Never attribute to stupidity that which is part of a system you don’t fully understand.”

A lot of things that seem unintuitive at first suddenly make sense when you see the whole picture, and it’s really, really hard to see the whole picture. Certainly there are mistakes that people make on the individual level, but when you’re talking about really big systems with lots of moving parts (like the video game development economy), there’s a lot of stuff that it’s really hard to see.

This was something I learned about today that I thought was interesting, and thought might be worth sharing. Hopefully you found it interesting too.

1 comment