We left off yesterday trying to define “fun”. I spoke before about challenge and expression of mastery, two components of fun, and I want to mention them again briefly. The psychological approach says that the brain likes to learn and the ego likes to be recognized– this is the core of challenge and expression of mastery. To create fun, however, we cannot force someone to learn; it’s very difficult to have fun when coerced, and so rather than forcing players to learn, we merely provide challenges and payoffs for said challenges to encourage learning. Voluntary learning is fun. Expression of mastery is in a similar vein– we have moved past simply telling the player “great job!”, though many older games did exactly this. We instead provide high scores, online play, leaderboards, and other such external functions as a measurable demonstration of mastery. Achievements are an extension of this, and are part of the next part of the equation.

So.

Fun = Challenge + Expression of Mastery + ?

Yesterday, I talked about following the money, as it were. Tracing the paths followed by game devs allows us to see the things that are emphasized, where a lot of effort is put forth. These are not decisions made in a vacuum, nor are they made frivolously. Resources in game development are always tight and games vary so widely that a particular feature or concept that crosses games (like difficulty settings) are worth noting, because they hint at a crucial piece of the puzzle. This next part is what we see emphasized in advertising, with each new console generation, in sequels, in indie games, and even in mobile games and flash games.

I’m talking about Spectacle. The loud, bombastic, explosive deluge of a triple-A blockbuster or the serene, calming meditations of a variety of indie games or the simple, focused pleasure of a match-3 mobile game — even the flailing-in-the-living-room spectacle of games of the Wii, Kinect, PSMove, Dance Dance Revolution, etc. I would have once described this as “exploration of beauty”, which I think is still accurate but isn’t broad enough to cover the entire spectrum. Spectacle is a term pulled from a friend and former colleague of mine, who points out that pressing “the most fun button in video games”* is much akin to enjoying the gorgeous desert of Journey and finding fantastic vistas in Skyrim. Whether that spectacle is a particularly satisfying button, a perfectly tuned user interface, a breathtaking visual, a particularly evocative musical piece, or some combination of all of these isn’t important– whatever it is that makes you stop and stare, or say “wow”, or laugh with surprise and awe, that is spectacle. Spectacles inspire awe, and awe is fun.

Fun = Challenge + Expression of Mastery + Spectacle + ?

The last piece to the equation is something that my aforementioned friend would call “delight”, which is linked to spectacle in the same way that expression of mastery is linked with challenge. I agree with the general concept, but in the same way I think “spectacle” describes a broader spectrum than “appreciation of beauty”, I think that a better term than “delight” would be “catharsis”. Video games offer, in many ways, an emotional release, and work to both inspire and satisfy emotions. If spectacle inspires emotion, cartharsis satisfies it. One builds up, the other pays off.

In the end, we have this:

Fun = Challenge + Expression of Mastery + Spectacle + Catharsis

I think this fairly well covers the spectrum of games that are fun, while realizing and accepting that different people will like different games (but all of those game can be fun!). It also gives us ways of analyzing why a game is or isn’t fun. Fun is obviously subjective, but this gives us a framework to understand how games are fun for different people in different ways. Certain games also focus more or less on these various things.

As an example, three extreme points on the gaming spectrum: Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Angry Birds. All three of these are highly popular games and their players will tell you they’re fun, but why? Let’s see if we can break them down:

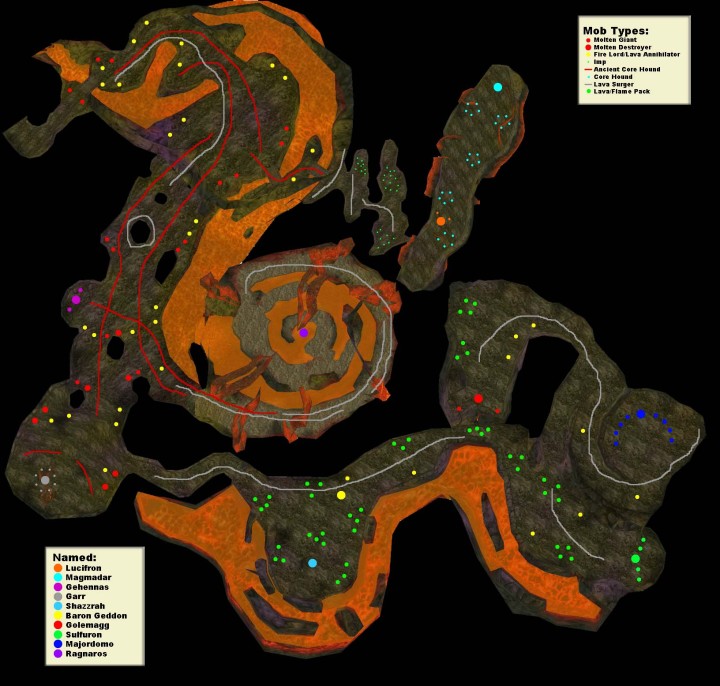

Challenge: Call of Duty requires excellent hand-eye coordination and fast reflexes, as well as good spatial reasoning. World of Warcraft doesn’t challenge the same skills in the same way, but does have a broader scope– challenging a player’s long-term commitment, their ability to comprehend and evaluate complex data, group coordination, pattern recognition and execution, and for many, social skills. Angry Birds also offers challenge, focusing heavily on spatial reasoning and pattern recognition as well as iterative experimentation. All three of these challenge different skills (with some overlap), and it’s thus unsurprising that the playerbases for each game differ very widely (again, with some overlap).

Expression of Mastery: Call of Duty allows players to test their skills against one another directly, as well as offering leaderboards and achievements for difficult goals. Its single-player levels also follow arcs of difficulty, allowing players to become good at fighting a particular enemy type or using a particular weapon and then allowing them to show off their skills with that weapon against foes they’ve become good at defeating. World of Warcraft follows many of the same arcs, with rare, powerful items replacing leaderboards and a heavier focus on team dynamics rather than individual skill. It also allows players to easily return to portions of the game they’ve grown past, displaying their power against enemies that once seriously threatened them — indeed, this behavior has for a long time been a cultural touchstone in MMOs. Angry Birds follows similar logic, with easier levels following difficult ones and ample opportunity to use different bird types effectively, often using fewer birds than allotted to win.

Spectacle: For Call of Duty, this is clear. Explosions, massive set pieces, loud music and flashy effects are on display. The game pits you against a variety of threats and offers you the chance to come out on top, showing off a variety of virtual locales and cinematic sequences along the way. World of Warcraft awes with the size and scope of its world– not only is the world large, but the roles a player can play in it vary widely, as do the ways in which mastery can be expressed. A highly skilled PvP warrior has a starkly different experience than a raid-focused mage, who in turn is wholly unlike the socially-oriented guild leader who spends most of their time talking to other players and growing/galvanizing their network. Angry Birds offers varied levels and a colorful, distinct art style, but for that game the spectacle is less inherent to the game itself and more a function of its convenience– Angry Birds can be played anywhere, at any time, quickly and easily, filling time that its players might otherwise spend bored or unoccupied. This transforms otherwise unsatisfying moments (where someone is forced to wait) into exciting ones (I can play Angry Birds!), giving the game an awe all its own.

Catharsis: Call of Duty’s spectacle is clear, and to some extent so is its catharsis– defeating enemies and beating the game is satisfying, but the more notable catharsis is more subtle. Call of Duty provides moments of high action followed by moments of relative calmness (on the player’s part), as non-interactive cutscenes play out, which in turn drive the high action. Cutscenes are a reward for succeeding at the action, and serve to pay off and then further set up the next action sequence. More subtly, the game is responsive and intuitive, two oft-overlooked elements that are very important. When a player’s emotional response is to move, or shoot, the game accomodates them without fuss, building and releasing that tension in every moment of gameplay. Similarly, World of Warcraft distinguished itself from its competition early on by having a highly polished, highly responsive game that enabled players to perform the actions they feel they should need to. It also pays off move execution, major milestones, and other interactions with sharp, clear audio and visual cues — the well-known “ding!” permeates the entire genre. Angry Birds has similar moments in its responsive controls and overall polish, but the real catharsis it offers is in the satisfaction it provides in what would otherwise be a boring moment, which itself is strong enough to inspire players to play at other times as well.

All four of the pieces of the “fun” equation are important, but different games emphasize them differently. It’s important to consider that different thresholds and paths for each of them will appeal to different people, or frequently the same person at different times. As developers, we can be informed by the things we are emphasizing in a game and how they might affect our audience (and how our intended audience might inform the things we emphasize). As players, we can better understand ourselves and make better-informed decisions about the games we like to play, since time and money are both limited resources.

I hope this was interesting or useful to someone. Let me know if you disagree, or if you think I missed something!

*For him, this is the “call assassins” button in Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood. For others, it’s the last button in that devastating ultra combo. For me, it’s frequently the “oh shit” button in MMOs.

.jpg?resize=478%2C331)