This weekend I played in my first tournament in my new local scene, which was awesome and a great way to ring in the new edition of Infinity.

I’ve had some strong opinions about ITS listbuilding in the past (even wrote a tactica on it), as well as which factions/sectorials are competitive in the format. For my first ITS 2015 tournament, I wanted to intentionally break a number of my own rules, as well as bringing a sectorial that I’ve had some unkind things to say about in the past as far as ITS viability. New city, new season, new sectorial.

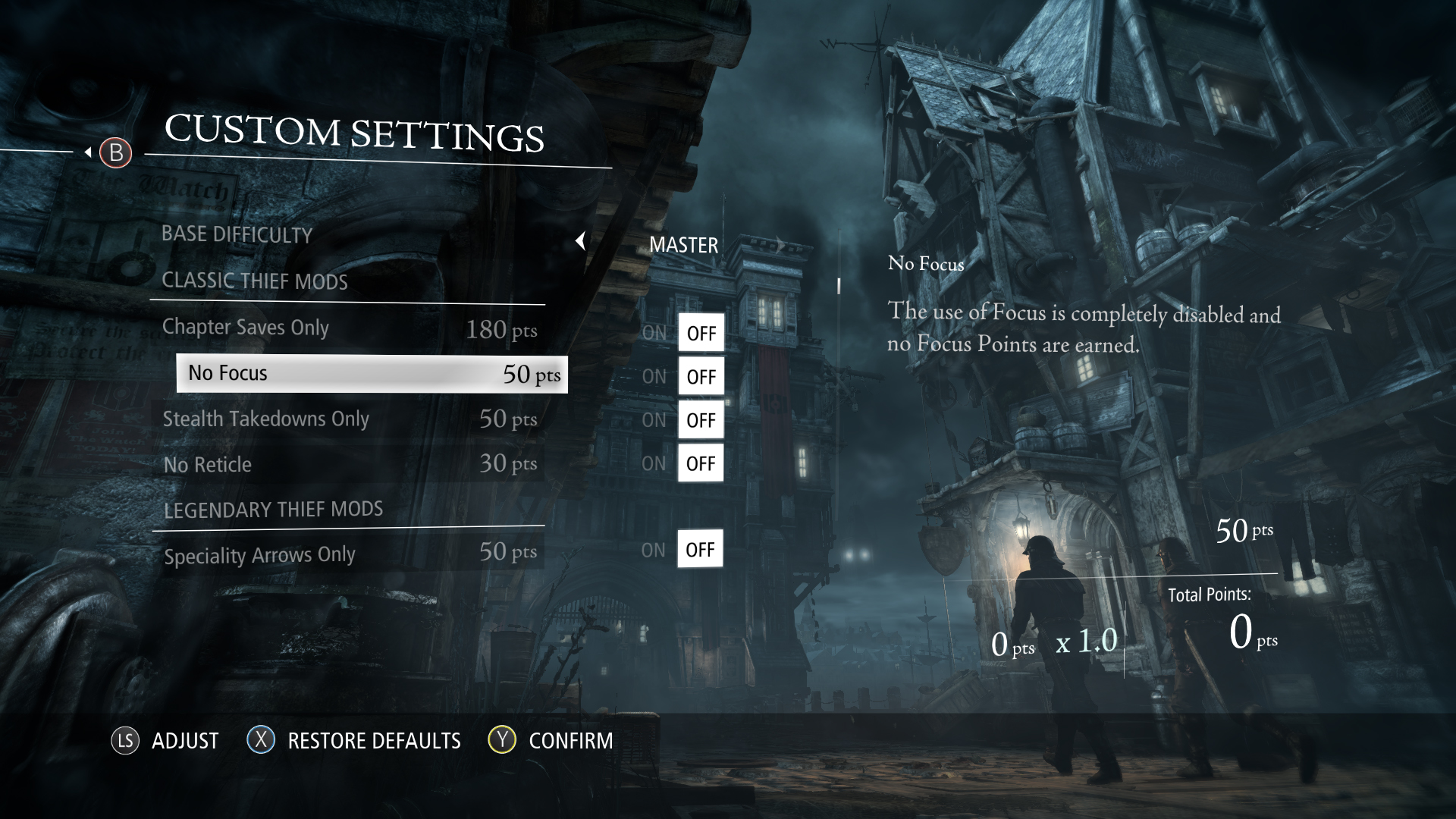

The tournament scenarios were Annihilation, Lifeblood, and Transmission Matrix, and I brought the Imperial Service. In N2, I felt like cheap, easy Kuang Shi wasn’t worth the lack of good specialists, expensive playmaking troops, and overall jankiness in listbuilding– vanilla YJ was more versatile and there was little reason to go for ISS. I also insisted on using models that I’d particularly disliked in N2, some of which are noticably different in N3– the Pheasant, the Crane, the Bao, and the Wu Ming.

Without further ado, my lists:

Imperial Service

Imperial Service──────────────────────────────────────────────────

WÚ MÍNG

WÚ MÍNG HMG / Pistol, Knife. (2 |

39)

WÚ MÍNG

WÚ MÍNG Combi Rifle, Light Rocket Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (1 |

37)

WÚ MÍNG (Forward Observer)

WÚ MÍNG (Forward Observer) Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Knife. (

31)

WÚ MÍNG (Forward Observer)

WÚ MÍNG (Forward Observer) Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Knife. (

31)

WÚ MÍNG

WÚ MÍNG Boarding Shotgun + 1 TinBot B (Deflector L2) / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

33)

SUN TZE Lieutenant (Advanced Command)

SUN TZE Lieutenant (Advanced Command) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers, Flash Pulse / Pistol, Knife. (

65)

KUANG SHI

KUANG SHI Chain Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

5)

KUANG SHI

KUANG SHI Chain Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

5)

NINJA Hacker (Assault Hacking Device)

NINJA Hacker (Assault Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Shock CCW, Knife. (0.5 |

40)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device) Combi Rifle + Light Smoke Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

13)

4.5 SWC | 299 Points

The new Wu Ming are exciting, and I wanted to run an HI link. I specifically included the LRL because I thought LRLs were awful in N2, and my plan was for this to be my primary list. It’s got hitting power, it’s got specialists, it’s got throwaway Kuang Shi, it’s got the ability to win initiative and give my deployment advantages.

My expectation was that the Ninja and Wu Ming link would do most of the work.

My second list:

Imperial Service

Imperial Service──────────────────────────────────────────────────

IMPERIAL AGENT (Chain of Command, X Visor)

IMPERIAL AGENT (Chain of Command, X Visor) Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Monofilament CCW. (

35)

CELESTIAL GUARD

CELESTIAL GUARD Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

13)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device) Combi Rifle + Light Smoke Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

13)

KUANG SHI

KUANG SHI Chain Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

5)

SOPHOTECT

SOPHOTECT Combi Rifle, D-Charges / Pistol, Knife. (

31)

YUDBOT

YUDBOT Electric Pulse. (

3)

HSIEN Lieutenant

HSIEN Lieutenant HMG, Nanopulser / Pistol, AP CCW. (2 |

61)

IMPERIAL AGENT Hacker (Assault Hacking Device)

IMPERIAL AGENT Hacker (Assault Hacking Device) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers / Pistol, DA CCW. (0.5 |

51)

BÀO TROOP

BÀO TROOP MULTI Sniper Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 |

30)

BÀO TROOP

BÀO TROOP MULTI Sniper Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 |

30)

BÀO TROOP (X Visor)

BÀO TROOP (X Visor) Boarding Shotgun, Contender / Pistol, Knife. (

28)

6 SWC | 300 Points

Bao, Crane, Pheasant, it’s everything I expected not to like. The Hsien HMG Lt was there because I tend to play very defensive, hidden Lts and I wanted to force myself to play something a bit more aggressive.

Neither list is more than 10 orders, and I was very light on the Kuang Shi. Both lists are focused on bringing things that only ISS can bring. Here’s how it went.

Game 1: Annihilation

My opponent was JSA, something that concerned me somewhat right away. I put a lot of stock in JSA as a competitive ITS faction, and a Keisotsu link can seriously threaten anything I had.

Furthermore, the table was a (fantastically gorgeous) cityscape, with multiple highly accessible levels and catwalks everywhere connecting things.

I pulled Telemetry (succeed at a Forward Observer roll) and Data Scan (use a Hacker to tag an enemy model) as my classified objectives, opt into the Wu Ming/Sun Tze list, and won the initiative roll, choosing to take first turn. My opponent took a slightly more advantageous side of the table with better sight lines and I deployed first.

I placed the Wu Ming link front and center, putting half the team on the bottom level and the LRL and one of the Observers up top, prone. Sun Tze went way off to one side, away from the bulk of my forces, with a Kuang Shi nearby to watch the approaches to him. The Celestial Guard went prone on top of a building, blocked by a much taller building, leaving plenty of space for her to drop smoke. I held back one of the Kuang Shi and my Ninja.

He deployed a full Keisotsu link on a rooftop, mostly prone, with a Missile Launcher pointed directly at my Wu Ming — problematic. He also dropped multiple extra Keisotsu, making it easy to refresh that link. More problematic. He also dropped a trio of Karakuri– unlinked but easily linkable. An engineer, sensor bot, EVO Repeater, and cheap repeaterbot all drop next, in hugely inaccessible locations. Rounding everything out was a Smart Missile bot. All told, it looked roughly like this:

Japanese Sectorial Army

Japanese Sectorial Army──────────────────────────────────────────────────

KEISOTSU

KEISOTSU Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

9)

KEISOTSU

KEISOTSU Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

9)

KEISOTSU (Forward Observer)

KEISOTSU (Forward Observer) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

10)

KEISOTSU (Forward Observer)

KEISOTSU (Forward Observer) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

10)

KEISOTSU

KEISOTSU Missile Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 |

14)

KEISOTSU

KEISOTSU Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (

9)

KARAKURI

KARAKURI Combi Rifle, Chain Rifle, D.E.P. / Pistol, Knife. (

35)

KARAKURI

KARAKURI Mk12, Chain Rifle, D.E.P. / Pistol, Knife. (

40)

KARAKURI

KARAKURI Heavy Shotgun, Chain Rifle, D.E.P. / Pistol, Knife. (

35)

KEISOTSU Hacker (Hacking Device)

KEISOTSU Hacker (Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

17)

TOKUSETSU KOHEI Engineer

TOKUSETSU KOHEI Engineer Combi Rifle, D-Charges / Pistol, Knife. (

14)

CHAĪYÌ Yaókòng

CHAĪYÌ Yaókòng Flash Pulse, Sniffer / Electric Pulse. (

8)

WÈIBĪNG Yaókòng

WÈIBĪNG Yaókòng Combi Rifle, Sniffer / Electric Pulse. (

16)

SON-BAE Yaókòng

SON-BAE Yaókòng Smart Missile Launcher / Electric Pulse. (1.5 |

18)

PANGGULING (EVO Repeater)

PANGGULING (EVO Repeater) Electric Pulse. (0.5 |

13)

4 SWC | 257 Points

Lots of specialists, particularly FOs, a very problematic Keisotsu ML that would be a problem, some tough Karakuri, oh, and enough points left over for an Oniwaban. A PH roll for deployment confirmed my suspicions, and without much backup for Sun Tze, I was concerned.

For the rest of my deployment, I put a Kuang Shi way on the opposite side of the board as Sun Tze, and the Ninja forward, right on the center line. I needed her to be able to tag someone, and I figured she would be one of my best chances to handle the Keisotsu.

Round 1.

That Keisotsu ML is a problem for me. My Kuang Shi impetuously move up, both hugging the sides of their respective buildings. I want the Wu Ming in a better position, so I pop smoke with the Celestial Guard to block the Keisotsu line of sight, then move the Wu Ming up, carefully. I use a Coordinated Order to reposition the CG, move a Kuang Shi up, move the Ninja up, and move Sun Tze somewhere a bit safer, still concerned about the probably Oniwaban. The CG drops more smoke to cover the Kuang Shi and the Ninja’s advance.

I’m able to get the Ninja and the Kuang Shi pretty far forward, but the Ninja can’t get close enough to hack anyone without some trouble, and the Kuang Shi can’t get close enough to threaten anyone without worrying about AROs. I go for broke and push the Kuang Shi forward, provoking a shot I didn’t see from the MK12 Karakuri while he got closer to chain rifle position. Miraculously, he survives the hit, and proceeds to put a chain rifle shot in the ML Keisotsu’s face, provoking shots from the SML bot and the Karakuri. Somehow, magically, he makes two of the three ARM saves, though the Keisotsu ML dodges and holds position, worried about the Wu Ming. Dogged kicks in, and I move forward and chain again, catching the ML Keisotsu and another combi Keisotsu, and taking more shots. The MK12 hits, the SML misses, and the Keisotsu ML fails his dodge and goes down to the chain rifle. The other Keisotsu is fine. The Kuang Shi makes its arm roll and keeps trucking. I’ve removed the major threat from the board, and I want to use this Kuang Shi until it dies. It rolls around taking chain rifle shots at various things largely ineffectually, finally putting a wound on the MK12 Karakuri before dying to return fire. I’ve got good ARO positions, and one of the worst threats to me is off the board. I call this turn good, as I’m out of orders, and prepare for incoming fire.

On his turn, my opponent repositions the sensor bot and the repeater bot to threaten the Ninja if she moves forward at all. The Oniwaban appears in front of the Wu Ming link, but being unable to walk up straight into melee without provoking boarding shotgun hits, he opts to use the boarding shotgun to catch two of the Wu Ming, who both fire back. 17s from the Oniwaban vs 16s from the Wu Ming leaves a wound on one of the Wu Ming Observers and a very dead Oniwaban. Wanting to get a foothold, he uses the Keisotsu on the roof to try to FO the Wu Ming, provoking Flash Pulses and LRL shots in response. The LRL misses, the first Keisotsu FO fails to mark, and the Wu Ming FO blinds the Keisotsu. Second Keisotsu does the same, manages to mark the LRL and not get blinded. Incoming SML missiles. First one misses. Second one the LRL Wu Ming saves. Third deals a wound to the LRL. Fourth kills the LRL outright, two wounds, super dead.

He swaps the link to the Karakuri, who start moving up the table. He’s worried about Flash Pulses from the Observers, so plays it cagey, risking chain rifle hits from the remaining Kuang Shi rather than getting blinded. In a stark bit of luck, the Kuang Shi puts a second wound on the MK12 Karakuri before dying horribly, and the resulting explosion puts a wound on the Combi Karakuri. She presses forward, shooting at the pair of Boarding Shotgun Wu Ming, wounding one and dying herself. The remaining Heavy Shotgun Karakuri goes for broke and rolls forward, firing her shotgun but getting crit in response, standing within half an inch of the wounded Wu Ming. Without any remaining orders, she stays put, the link is reformed with the Keisotsu, and they resposition slightly.

Round 2.

I’m in an okay position, minus the Karakuri in my face. I’m going to eat some unfortunate damage either way, so I start by taking a shot at the Karakuri. Boarding Shotguns are nasty, but she explodes. My FO Wu Ming is a hero, though, and survives both her shotgun blast and her explosion. Now, time to get work done.

The Ninja madly dashes into my opponent’s DZ, getting Discovered along the way but ending in relative safety. She’s in sight of a Keisotsu, so shoots him and moves closer to the EVO Repeater, the only safe approach for her to Hack-tag a target. She moves into position and provokes a Brain Blast Hacking attack in ARO, from the Keisotsu Hacker. She fails, but makes her BTS save. I don’t like the risk, and I want the classified, so I go straight for hacking the EVO repeater. I succeed and the Keisotsu fails to Brain Blast me, lucky for me. My Wu Ming move up a bit to try to FO one of the fallen Keisotsu, succeeding and finishing off my other Classified. With some orders left and my Ninja Hacker doing pretty okay, she Brain Blasts the Keisotsu Hacker, dropping him, and steps to the side to shoot at some remotes, somewhat ineffectually. She goes down to a return crit from the sensor bot.

On his turn, the sensorbot and the repeater move forward towards my HVT. I manage to destroy the sensorbot with HMG fire as it approaches, but the Repeater is doing all right. At this point, time is called, and he finishes out his turn by moving forward to secure my HVT, who is undefended.

I’ve killed 210 points of his, and he’s killed 87 points of mine. I finish the game 9-5, a solid start to the day.

Game 2: Lifeblood

I have no Anti-Materiel in the Wu Ming list, but that’s okay, I brought the Bao list specifically for this. Two specialists who can blow up crates (Crane Hacker with MULTI Rifle, Sophotect with D-Charges), lots of Anti-Materiel from the Bao, good times.

I pull Sabotage and Data Scan, meaning my already-busy Sophotect and Crane are going to have even more work to do. There are only three specialists in this list, and one of them is kind of stuck with the Bao, so kind of a non-entity.

My opponent is also playing ISS, and we’re on a table with a really nice tower on one side. I win initiative, take the side of the table with the tower, and my opponent is immediately concerned. Guessing (correctly) that I have a powerful sniper team ready, he decides to force me to make the first move, opting for second turn. I’m okay with this.

He deploys extremely defensively, keeping almost everything covering each other and out of sight of most of the board. He drops a Celestial Guard link with a sniper, a hacker, and some shotguns. A Rui Shi, a Lu Duan, another unlinked Celestial Guard, and Sun Tze. His list looks something like this:

Imperial Service

Imperial Service──────────────────────────────────────────────────

CELESTIAL GUARD

CELESTIAL GUARD MULTI Sniper Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 |

21)

CELESTIAL GUARD

CELESTIAL GUARD Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Knife. (

12)

CELESTIAL GUARD

CELESTIAL GUARD Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Knife. (

12)

CELESTIAL GUARD Hacker (Hacking Device)

CELESTIAL GUARD Hacker (Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

21)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device) Combi Rifle + Light Smoke Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

13)

LÙ DUĀN

LÙ DUĀN Mk12, Heavy Flamethrower / Electric Pulse. (

22)

RUI SHI

RUI SHI Spitfire / Electric Pulse. (1 |

21)

SUN TZE Lieutenant (Advanced Command)

SUN TZE Lieutenant (Advanced Command) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers, Flash Pulse / Pistol, Knife. (

65)

CELESTIAL GUARD

CELESTIAL GUARD Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Knife. (

12)

3.5 SWC | 199 Points

I guess that with the 100 points remaining, there’s a Ninja Hacker and something beefy.

I deploy extremely aggressively. Crane on one side, Sophotect on the other, Bao Snipers in the tower, covering the entire board, spread out enough that one circular template can’t tag both. There’s also nothing that can see my troops, so I plan an extremely aggressive first turn.

My opponent drops a Hsien HMG, prone, on his side of the table. About as expected.

Round 1:

I get really aggro, really fast. The Kuang Shi moves forward, and I burn multiple coordinated orders pushing it, the Crane, the Sophotect, and the Celestial Guard w/Smoke up and towards boxes. I can move around with relative impunity, so I get as much done as possible– four boxes searched and Sabotage complete, with the Sophotect hanging out midfield near the last two boxes (that scattered next to one another), and the Crane and CG in cover watching the board. I’ve still got a handful of orders after doing all of this, so I push the Kuang Shi forward into the Celestial Guard link. I can’t quite get the angles I want, so instead of chain rifling I take a risk and jump into the middle of them, figuring that if I can Explode I’ll take out several at once. AROs straight up kill the Kuang Shi, no chance to explode, and this is a hint as to how the next turn is going to go.

My opponent looks at the board, disliking what he sees. Snipers are pinning him down badly, and they have MSV2, so he can’t use smoke to advance. He decides to get into some firefights. The Celestial Guard link repositions, and he spends an extra order moving while prone to ensure that he can get cover when shooting with the sniper. The sniper takes a shot at my Crane and drops him immediately, then repositions to shoot the Sophotect, killing her, the Celestial Guard, killing her as well, then both Bao, killing both of them. With his last orders, the Ninja Hacker I expected pops out and tags both center boxes near where the Sophotect died, and hunkers down.

Round 2:

Ouch. I’m down a LOT of orders, and I can’t complete Data Scan. This turn is about damage control, and I only have four orders to work with. I need to get lucky. It’s Contender time.

The X-Visor on the remaining Bao is ultra useful, as I use my four orders this turn to reposition the Bao and take shots at the boxes. Dice are absolutely on my side and I destroy four boxes scoring three crits in total and nullifying my opponent’s chance at a tie. The last shot leaves the Bao hanging out in the wind and he gets obliterated by the CG Sniper, but not before scoring that last vital crit. My Hsien spends his Lt Order and ineffectually sprays at the CG, who duck for cover, prone and out of sight.

My opponent is displeased that my turn went as well for me as it did, and spends orders covering the Hsien advance and blowing up the two boxes he’d marked, then moving the Ninja up to Data Scan my Hsien, then take several orders to eventually Immobilize him. He also leaves the ninja close enough to secure my HVT, knowing that I can’t really do anything about it. He finishes his turn by popping the Hsien up to cover the board. Ew.

Round 3:

Three orders, one immobilized Hsien, no way for me to get my other classified. I’ve won this, but I want to push for points. It’s not to be, though, as my Hsien can’t manage to break free of Immobilization and get far enough through the aggressive Ninja’s hacking to reach my opponent’s HVT and secure it. I flail for four orders and end turn. At this point, time is called.

My opponent looks at the board and considers that there’s nothing he can do on his turn to get more points than he had, so immediately ends turn.

Final score: 7-4. My first-turn push saved that game, and my dominant board position wasn’t. Still, a win is a win, and Lifeblood is rather hard to score points on.

Game 3: Transmission Matrix

Final game of the day, and I’m doing pretty well. I’d planned on using the Wu Ming list for this, and in fact had brought the Tinbot for precisely that reason, but the spate of hacking against the Hsien made me less than thrilled about exposing my HI link to constant hacking.

When I see the table, I note another tower, though one that’s blocked by a huge building in the middle. Still, it’s a good Bao sniper perch, so I decide it’s Bao time again. My opponent is playing Morats, so I’m not really concerned about surprise camo attacks.

I draw Sabotage and Data Scan again, perfectly all right with me. We roll initiative and I lose. My opponent takes first turn, I take deployment and choose the side with the tower. I’m perfectly okay going second in this mission.

My opponent drops a bunch of Morats. Something like this, overall:

Morat Aggression Force

Morat Aggression Force──────────────────────────────────────────────────

MORAT Hacker (EI Hacking Device)

MORAT Hacker (EI Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

22)

DĀTURAZI

DĀTURAZI Combi Rifle + Smoke Light Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Shock CCW. (0.5 |

21)

DĀTURAZI

DĀTURAZI Chain Rifle, Grenades, Smoke Grenades / Pistol, AP CCW. (

14)

DĀTURAZI

DĀTURAZI Chain Rifle, Grenades, Smoke Grenades / Pistol, AP CCW. (

14)

DĀTURAZI

DĀTURAZI Chain Rifle, Grenades, Smoke Grenades / Pistol, AP CCW. (

14)

ZERAT

ZERAT Combi Rifle + Light Flamethrower, Antipersonnel Mines / Pistol, Knife. (

21)

ZERAT

ZERAT Combi Rifle + Light Flamethrower, Antipersonnel Mines / Pistol, Knife. (

21)

T-DRONE

T-DRONE Smart Missile Launcher / Electric Pulse. (1.5 |

18)

GAKI

GAKI AP CCW. (

4)

RASYAT (Martial Arts L3)

RASYAT (Martial Arts L3) Boarding Shotgun, D-Charges, Zero-V Smoke Grenades / Pistol, DA CCW. (

28)

MORAT Hacker (EI Hacking Device)

MORAT Hacker (EI Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |

22)

RODOK

RODOK HMG / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 |

27)

RODOK

RODOK HMG / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 |

27)

RODOK Paramedic (MediKit)

RODOK Paramedic (MediKit) Boarding Shotgun, Antipersonnel Mines / Pistol, Knife. (

21)

RODOK Lieutenant

RODOK Lieutenant Combi Rifle, 2 Light Shotguns / Pistol, Knife. (

26)

6 SWC | 300 Points

I don’t really know Morats very well, so I see two potential links, the Daturazi starting in a link, and a pretty widely divided order pool.

I deploy very carefully, securing one antenna with the two Celestial Guard and putting the Sophotect in position to claim the other. The Hsien and Crane are carefully positioned in the thin strip between the two hacking areas of the antennae. There’s a huge wall as part of a building along the halfway point, with the antenna just inside. My plan is to get my troops to contest that middle one, hold my two, and keep things clear.

Round 1:

My opponent’s Gaki moves up, as one does, and he moves his Daturazi forward to get better positioning. I can see one with a Bao sniper, so shoot and drop it through the dodge. Next, he swaps the link to the Rodoks and jumps one up to get into an HMG battle with my Bao link. The Bao stay frosty and drop the Rodok with a well-placed shot. The Rodok paramedic starts jumping, however, to revive the fallen Rodok, succeeds on the second try, and a second sniper-vs-HMG battle ensues. This time, the Bao hits twice and puts one of the Rodok HMGs down for good, straight to dead.

A Zerat moves forward to threaten the Sophotect, and I completely miss that I have a shot at her with the Bao sniper through a window. However, as she opens fire with the Zerat, the Sophotect manages to answer with a crit on an 8, dropping the Zerat quite effectively. My opponent goes to move in with the second Zerat, but this time I’m paying attention and he can’t safely move forward without taking sniper fire, so he hangs tight. A number of models reposition, but I can’t see any of them. He reforms the link with the Daturazi.

On my turn, the Kuang Shi moves forward, then a coordinated order with the Crane, Hsien, and Sophotect puts them all further up the board, with the Sophotect contesting an antenna. I’m not careful enough with the Hsien, and he gets immobilized. I carefully scoot the Crane up to get in range to Data Scan a Rodok through the wall and manage to succeed. He then moves to within 4″ of the antenna and is promptly hacked and immobilized. I swing around with the Kuang Shi and start chain rifling Rodoks. A few dodges are attempted, but I’m able to drop the combi Rodok, leaving the center antenna uncontested. I score two points in the first round..

Round 2:

My opponent swings the Gaki around towards the Kuang Shi, and I chain rifle it on the way in. It dodges, but the HMG Rodok is caught in the blast and goes down. The Paramedic Rodok brings up the Combi Rodok. At this point, the Rasyat drops in right behind the Sophotect. He can’t get to her without being seen by the sniper, so he drops Zero-V Smoke, but can’t put it in a position where he can threaten the Sophotect without getting shot at by a Bao or CG, so he hangs tight, repositioning to a corner where he can get cover. The Gaki melees the Kuang Shi, who manages to successfully dodge out of melee. He repositions to ensure antenna coverage. He also Spotlights my Crane and drops smart missiles on it, leaving it unconscious, and drops a mine with a Rodok.

On my turn, I get squirrelly. The Kuang Shi has to move towards the Gaki, triggering the mine, but this is okay, and he manages to chain rifle the Gaki and HMG Rodok along the way.The HMG Rodok finally dies for real, but the Gaki is okay. I bring a Bao with a boarding shotgun around to threaten the Rasyat, using a boarding shotgun and getting outsmoked. I take a long shot with the CG and put my own smoke down, blocking sight to a building entirely on my opponent’s half of the board. I then go nuts with my Sophotect, moving forward and shooting the Gaki, who explodes but catches no one. While moving along with her Yudbot, the Sophotect manages to reach the building, place and detonate a D-Charge, and get back, healing the Crane along the way and retaining cover against the Rasyat. The Hsien, no longer immobilized, moves up to within 4″ of the antennae and declares Reset to avoid being Hacked, but fails and is Immobilized again. At the end of my turn, I control three antennae to my opponent’s two, and score two more points.

Round 3:

My opponent brings both Rodok forward to contest the antenna, one of whom shoots the Sophotect, causing a wound. Having made a save, she fails Guts and hops the wall, keeping cover from the Rodoks but not the Rasyat. The Rasyat shoots her. Alas. Hackers Spotlight my BSG Bao, succeeding on the second try and dropping smart missiles on him until he is severely dead, breaking my link.

On my turn, I pull the Pheasant out and spend my entire order pool bringing him around to shoot the Rasyat in the back with a boarding shotgun, then moving forward to contest the antenna. Nothing else matters here, I just needed that last one. I’ll pause here to point out that this was a textbook case in which the Pheasant could actually have used his monofilament CCW, and I STILL DIDN’T because the shotgun was a better option.

With two 55+ point HI contesting the center antenna, the Rodoks can’t compete, and I take 3 antenna in the final turn, for a maximum score of 10.

Results and Thoughts:

ISS performed really well. I was running 10-order lists with bare minimum specialists– three in one list and effectively two in the second (the CoC Pheasant doesn’t really count, since he’s tied down by the Bao).

Bao are damn good. They serve little purpose other than a sniper link, but on the right table that’s all you need; they provide deadly AROs while the rest of your list does work. I don’t know what I would drop to get to a full, scary 5-man link, but I don’t think it’s that necessary. I wish there were more Bao profiles, though.

The Crane is a serious workhorse, as is the Sophotect. I already knew that about the Sophie, but the Crane is surprisingly badass, despite getting ignominiously blown away by a Celestial Guard.

Wu Ming give opponents fits. They can’t get close, because boarding shotguns, but I also have HMGs to scare you with. I don’t know if I think the LRL is worthwhile, but I definitely feel like the Tinbot isn’t. Breaker ammo just doesn’t impress.

Overall, I had a great time, taking away first place with a total score of 26 OPs and several really good games.

.jpg)

Imperial Service

Imperial Service

10

10  0

0  2

2 WÚ MÍNG HMG / Pistol, Knife. (2 | 39)

WÚ MÍNG HMG / Pistol, Knife. (2 | 39) SUN TZE Lieutenant (Advanced Command) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers, Flash Pulse / Pistol, Knife. (65)

SUN TZE Lieutenant (Advanced Command) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers, Flash Pulse / Pistol, Knife. (65) KUANG SHI Chain Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (5)

KUANG SHI Chain Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (5) NINJA Hacker (Assault Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Shock CCW, Knife. (0.5 | 40)

NINJA Hacker (Assault Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Shock CCW, Knife. (0.5 | 40) CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device) Combi Rifle + Light Smoke Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |13)

CELESTIAL GUARD (Kuang Shi Control Device) Combi Rifle + Light Smoke Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 |13) IMPERIAL AGENT (Chain of Command, X Visor) Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Monofilament CCW. (35)

IMPERIAL AGENT (Chain of Command, X Visor) Boarding Shotgun / Pistol, Monofilament CCW. (35) SOPHOTECT Combi Rifle, D-Charges / Pistol, Knife. (31)

SOPHOTECT Combi Rifle, D-Charges / Pistol, Knife. (31) YUDBOT Electric Pulse. (3)

YUDBOT Electric Pulse. (3) HSIEN Lieutenant HMG, Nanopulser / Pistol, AP CCW. (2 | 61)

HSIEN Lieutenant HMG, Nanopulser / Pistol, AP CCW. (2 | 61) IMPERIAL AGENT Hacker (Assault Hacking Device) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers / Pistol, DA CCW. (0.5 | 51)

IMPERIAL AGENT Hacker (Assault Hacking Device) MULTI Rifle, 2 Nanopulsers / Pistol, DA CCW. (0.5 | 51) BÀO TROOP MULTI Sniper Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 | 30)

BÀO TROOP MULTI Sniper Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 | 30) Japanese Sectorial Army

Japanese Sectorial Army KEISOTSU Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (9)

KEISOTSU Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (9) KARAKURI Combi Rifle, Chain Rifle, D.E.P. / Pistol, Knife. (35)

KARAKURI Combi Rifle, Chain Rifle, D.E.P. / Pistol, Knife. (35) TOKUSETSU KOHEI Engineer Combi Rifle, D-Charges / Pistol, Knife. (14)

TOKUSETSU KOHEI Engineer Combi Rifle, D-Charges / Pistol, Knife. (14) CHAĪYÌ Yaókòng Flash Pulse, Sniffer / Electric Pulse. (8)

CHAĪYÌ Yaókòng Flash Pulse, Sniffer / Electric Pulse. (8) WÈIBĪNG Yaókòng Combi Rifle, Sniffer / Electric Pulse. (16)

WÈIBĪNG Yaókòng Combi Rifle, Sniffer / Electric Pulse. (16) SON-BAE Yaókòng Smart Missile Launcher / Electric Pulse. (1.5 | 18)

SON-BAE Yaókòng Smart Missile Launcher / Electric Pulse. (1.5 | 18) PANGGULING (EVO Repeater) Electric Pulse. (0.5 | 13)

PANGGULING (EVO Repeater) Electric Pulse. (0.5 | 13) LÙ DUĀN Mk12, Heavy Flamethrower / Electric Pulse. (22)

LÙ DUĀN Mk12, Heavy Flamethrower / Electric Pulse. (22) RUI SHI Spitfire / Electric Pulse. (1 | 21)

RUI SHI Spitfire / Electric Pulse. (1 | 21) Morat Aggression Force

Morat Aggression Force MORAT Hacker (EI Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 | 22)

MORAT Hacker (EI Hacking Device) Combi Rifle / Pistol, Knife. (0.5 | 22) DĀTURAZI Combi Rifle + Smoke Light Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Shock CCW. (0.5 | 21)

DĀTURAZI Combi Rifle + Smoke Light Grenade Launcher / Pistol, Shock CCW. (0.5 | 21) ZERAT Combi Rifle + Light Flamethrower, Antipersonnel Mines / Pistol, Knife. (21)

ZERAT Combi Rifle + Light Flamethrower, Antipersonnel Mines / Pistol, Knife. (21) T-DRONE Smart Missile Launcher / Electric Pulse. (1.5 | 18)

T-DRONE Smart Missile Launcher / Electric Pulse. (1.5 | 18) GAKI AP CCW. (4)

GAKI AP CCW. (4) RASYAT (Martial Arts L3) Boarding Shotgun, D-Charges, Zero-V Smoke Grenades / Pistol, DA CCW. (28)

RASYAT (Martial Arts L3) Boarding Shotgun, D-Charges, Zero-V Smoke Grenades / Pistol, DA CCW. (28) RODOK HMG / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 | 27)

RODOK HMG / Pistol, Knife. (1.5 | 27)