A bit of a personal post today. Bear with me.

It hasn’t been a good year. I suspect a lot of people can relate with that feeling in general; for me it’s been a pretty steady grind with very few (highly cherished) bright spots. It’s been an extended exercise in coping, and staying not just functional but managing to excel in what I can despite it all. I’ve basically had most of what I used to consider my identity removed and don’t have a lot to replace it, paired with an uncertainty about my future that colors pretty much every decision I make. As of this writing, none of the likely outcomes look great; I’m basically hoping that in the next couple of months, something changes from what I’ve been doing for the last 18+.

Friends and family ask me how I’m doing, and for months it’s been pretty much the same answer: no change. I appreciate the sentiment, but rehashing my situation over and over doesn’t make me feel better about it. It’s not something I bring up, because I value my friends and family greatly and I know how much it sucks to have someone close to you suffer and be able to do nothing about it. You want to talk, you want to do something, but there’s nothing you can contribute so you’re relegated to making sympathetic sounds and looking sad, or if those gestures feel hollow, making any recommendations you can think of. As much as I don’t like being on the receiving end of any of that, I don’t really know how else to respond.

Someone asked me a different question, recently. I was asked “how are you coping?”, and when I responded with the usual “oh, you know, as best I can” the followup was pointed: “No, I mean what are you doing to cope, how are you mentally handling everything?”

It’s an interesting question, and one that had been riding in my subconscious for a while. It’s a question I appreciate, because it’s something I can articulate, and it doesn’t feel like the same circular thrashing of “things are bad, I don’t know what else I can do to make them better”. As a followup, my friend mentioned that I haven’t been posting here as much anymore– my reasoning was that I don’t trust my mental state enough to stay objective about the things I write; maybe that isn’t so healthy. So, here we are. Here’s the answer I gave about how I cope with stress:

I’m a very results-driven person. It’s a core that runs deep, something I’ve inherited from my parents. Being overwhelmed by stress and completely shutting down isn’t productive, it’s a response that, however powerful, runs counter to the fiber of my being; even my subconscious won’t let me do it. This would probably boil over if I didn’t have really great release valves built in somewhere.

I developed release valves in martial arts. I started my martial arts training as The Fat Kid; I couldn’t even complete warm-ups without being exhausted, and I was in the same space as others who completed the same exercises without breaking a sweat. Pair this with the fact that failure has never been acceptable for me, and you’ve got a stressful experience waiting to boil over. My instructor keyed in on this and focused on it, he first taught me to redirect that stress into motivation, watching to make sure I got better at it. I was eventually in good shape, which is when the real training began. My instructor would occasionally provoke me, try to get through my usual emotional wall, to provide motivation. Knowing I could react in anger and lash out was never in question for me, I just had too much self-control to ever let myself do it, and I avoided ever coming close. I tamped down my negative emotions to an extreme, and tightly channeled them through very controlled channels, if at all.

Flash forward to undergrad, where I had my first taste of failure. Going from breezing through high school to the much more intense and rigorous curriculum of a very competitive college was a shock, and not one I emerged from unscathed. At the time, I had it suggested to me that I should consider dropping out, that maybe my chosen school was too hard for me, and that, perhaps, I had bitten off more than I could chew. I think part of me was despondent, ready to give up and give in just so the stress would end, but another part of me was enraged. I was angry at myself for failing, angry at the suggestion that I might not be good enough, angry at the obstacles in my way, and years of martial arts training kicked in. Of the two emotions I was facing, one of them felt productive and one of them didn’t. I channeled white-hot anger into my studies for a year and brought my GPA up nearly two full points, and graduated on time.

Anger is probably a misleading word; it has a lot of negative connotation. I could also use “passion” to describe it, passion for myself, passion for self-actualization, passion for growth, passion for my interests and motivations. I see anger and passion as not terribly different, and useful but needing to be kept under control. I’ve gotten good at controlling it.

For myself, when faced with apparently insurmountable difficulty, I can see despondency and passion looming on the horizon, and of the two, passion is productive and it’s something I know how to channel. It gives me energy and drive to push through, and it sublimates well into excitement and joy when I do finally push through. It’s not without cost; without good outlets for energy it tends to build, and I tend to retreat from people and things when it does, because I know it’s sitting closer to the surface and can be provoked more easily. When I’m stressed and don’t have an energy outlet (like work), I tend to avoid putting myself in more stressful situations because I want to minimize that buildup of energy, and because I don’t want spillover to affect anyone around me. I don’t want to snap at people, and when I’m extremely stressed and can’t do anything about it, I’m aware my tight controls are weaker, so I try to avoid situations where I might snap.

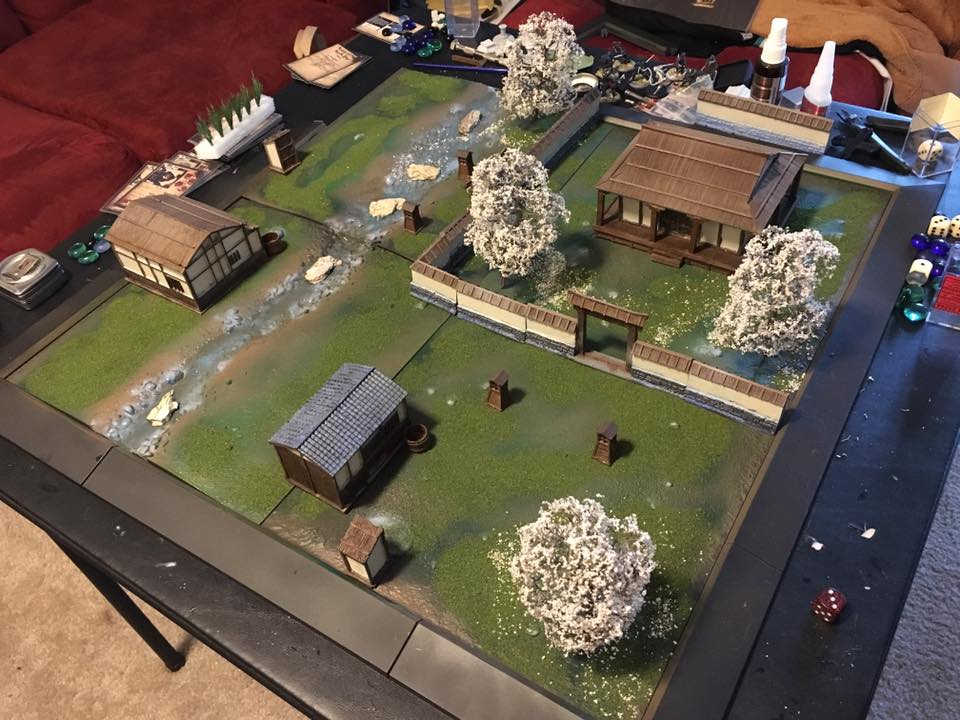

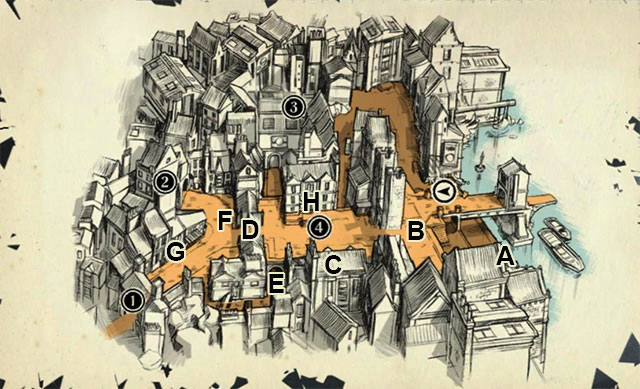

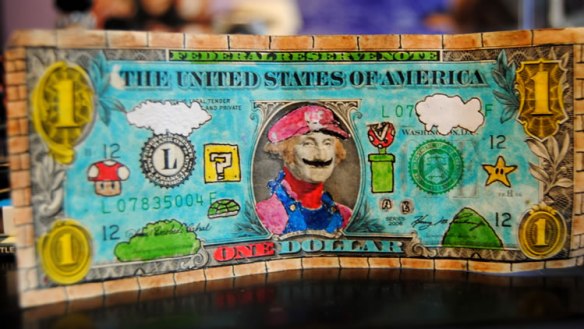

I cope with stress by channeling it, and I tend to keep a few side projects going at all times to have outlets. What I’m starting to run into lately is that those side projects feel meaningless and arbitrary in the shadow of my actual situation, so putting time and energy into them doesn’t help. Also not helping is the rest of this year, everything going on that *isn’t* directly part of my day-to-day life that’s just a massive garbage fire. I try not to watch the news but it’s difficult to avoid.

I’m not really sure how this ends. I can maintain, for now. I can probably maintain for as long as the idea of quitting just makes me angry, and want to try harder.

Maybe that’s enough. Maybe that’s just what “perseverance” is.