I keep working on Japanese, though my pace has slowed down a little bit. Not having the weekly tutor to force me to keep up means I study less, and with classes having started up again, my focus is going there first and foremost. I have, however, started supplementing my use of the Genki textbook with Rosetta Stone, which has been interesting.

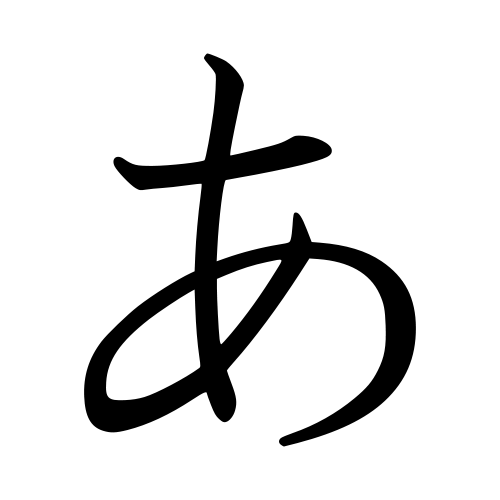

Before I talk about Rosetta Stone, I should recap my studies thus far. I started studying Japanese about twelve weeks ago now. The first two weeks were me memorizing kana, specifically hiragana, and I’ve gotten to the point where I can just read them now. I’m not fast, but I don’t need a reference anymore. I spent the third week on katakana and some basic vocabulary and phrases. I really need to spend a lot more time with katakana, because it comes up a LOT in writing, and I really didn’t give it the same amount of time as hiragana. I find it a lot harder to memorize, because the syllables are visually very similar, and as a result my ability to read katakana is HORRIBLE.

After the first three weeks, I took about a month’s worth of lessons with a tutor, during which time we were able to blaze through the entire first Genki book. It was a whirlwind, and while I picked up concepts extremely quickly and can suss out grammar, the pace was too fast with too many new words being introduced for me to keep up with the vocabulary. After the last tutoring session, I took about two weeks off to process, which in retrospect was a horrible mistake. I didn’t lose much if any of the structural stuff I learned, but my already limited vocabulary atrophied, and my pronounciation suffered. I also lost my tenuous grasp of katakana, though I’d ingrained hiragana enough that I didn’t lose it, I just got slower.

Since then, I’ve been working with Rosetta Stone, and am going to return to doing exercises from the Genki workbook as well. Rosetta Stone is a very different structure for learning, and it works pretty well for me, but I’ve read a LOT of criticism about it. Since a few people have commented that they’ve liked to see my learning process, I kind of want to break down how I feel about Rosetta Stone, in case it’s helpful for anyone eyeing it but concerned about the (rather high) price.

The teaching method appeals to me, as I’ve mentioned before, because it avoids using English entirely. Pretty much everything is kana and images that you match or speak. I like this, because it removes all of the English-language distractions and forces me to connect concepts with Japanese directly, rather than using English as a go-between. You can pick up a free app that has the first handful of lessons for a variety of languages on mobile devices, to see what I’m talking about, and it’s what gave me my initial foothold into Japanese.

One of the interesting things about Rosetta Stone is that it doesn’t at any point explicitly tell you what you’re saying or what the pieces of the sentences are. It slowly becomes clear as you work, but you’re looking at hours of work before you can see the shape of a sentence, because you may or may not be picking up which words mean which things, and how they’re all fitting together. It won’t stop you from progressing in the lessons, but it’ll make it difficult to feel like you’re making tangible progress until you’ve put a few hours into it. It’s an intentional bit of design, it forces you to process the sentences as a whole and work to make sense of them, so you retain the information better. Rather than telling you how to say something, it has you say something and forces you to figure out what you just said from context clues. If I wasn’t aware of that style of teaching and how effective it is, I’d probably find it very frustrating. Certain critical reviews describe it as “nonsense”, which to me sounds like frustration with the style; everyone learns differently, and while this works for me, it likely doesn’t for other people.

I’m glad I have both the textbook and other translation aids available to me as well. It lets me see interesting things that Rosetta Stone teaches me how to use, then look up the structure, how they’re being used, and what they actually mean. It’s resulted in a lot of spin-off lessons, where I learn about the different ways to use pronouns because Rosetta Stone switched pronouns on me. A great example is when the book switched from using 男の人 (おとこのひと, “otokonohito”, man) to 彼 (かれ, “kare”, he), which changes the sound of sentences significantly but can be used functionally identically in a sentence. It uses a lot of the same basic sentences with various swaps to help build vocabulary while giving you a sense of structure.

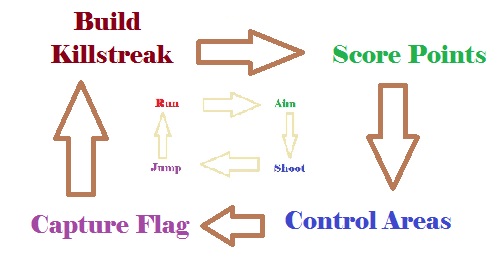

For example, you’ll have one exercise where a sentence might be “The [boy/girl/woman/man] runs,” where the exercise is appropriately recognizing the words for “boy”, “woman”, “man”, and “girl”. The next exercise might be “The woman [runs/eats/reads/swims],” where the exercise is about recognizing the verb. It builds on the structure of the first sentence and swaps out a different part, so you slowly get a feel for all of the different pieces. The whole thing could probably use a tutorial, but once you realize what it’s asking you to do it’s pretty intuitive.

The real question is “is it worth $200+”? It’s not a question I can really answer for everyone, obviously, but I can explain my approach. I tend to look at how much content I’m getting and how valuable the content is. The demo for the software should give you a pretty good idea of whether or not the content is valuable for you; it may work well with how you learn or it might not. As far as amount of content goes, the program is structured in chunks. The smallest segments are called “lessons”, and range from quick, 5-minute items to 30-minute “core lessons”. There are a handful (six to fifteen or so) 5- and 10-minute lessons after each 30-minute “core lesson”, and after four core lessons and a final refresher at the end, you’ve completed a “unit”. There are four units, each comprised of four core lessons and numerous mini-lessons, all of which make up a “level”. The Japanese module for Rosetta Stone contains three levels. All in all, that’s 3 levels, 12 units, 48 core lessons. I tend to take slightly less time per lesson than the estimated time. By the estimated times for each segment, it works out to 60-120 minutes per core lesson+mini-lessons. If we lowball that and say it’s about 4 hours per unit (kind of a fast pace, but it’s close to the speed I’m going at), that’s on the order of 48-50 hours of lessons.

Assuming you don’t repeat any lessons (i.e. do each one once and never look at it again), for the currently-listed $209 for the software (Rosetta Stone site, cheaper on Amazon), you’re paying about $4.40 per hour. As a point of reference, an inexpensive Japanese tutor in my area is on the order of $30 an hour. It’s certainly not as personalized an experience as a tutor, and I’m really glad I spent time with my tutor because it let me focus on certain specific things, but as far as a time/money value proposition, it’s better than going to go see a movie. Whether that’s time/money well spent is probably up to the individual.

Currently, I’ve gotten to the point where I can watch subtitled anime and clearly hear sentence structure, though my vocabulary isn’t close to keeping up. I can tell when the translation is different from the audio, and I’ve started being able to pick up on nuances that enrich the experience for me. It’s really funny to me, for example, how in One-Punch Man, Genos’ speech to Saitama is hyper-formal and very precise, whereas Saitama’s responses are incredibly laid back and almost too casual. It lends a lot to both of those characters that I’d otherwise have trouble picking up on just from the text and the tone of voice.

I’m a little ways into the third unit of Level 1, so I’ve still got a ways to go. I’ll keep commenting here as I get to other interesting pieces.